To be a monster

Identities for our everyday life

Privacy and visibility

a LGBTQIA+ zine

The idea of making a zine about privacy for LGBTQIA+ people came from conversations that repeated the same story of violence and scrutiny: after being pulled out of the closet, people have their social lives controlled by their families, their online or phone communications monitored or restricted, and their friendships and love relationships closely watched or completely forbidden.

We began to write this zine based on the belief that basic notions of digital security can help us move more freely in our digital environments and avoid exposure and repression in our households, workplaces, schools, and social environments. If, for many people, coming out is a political gesture, being able to pick when and how we share our sexual identities is certainly our right.

Another factor that motivated this zine was the intensification of the online activity by conservative groups and hate speakers. Online threats, attacks and the disabling of pages and profiles are a part of many activists’ daily routine, in a strategy that silences voices, violates freedom of expression and impacts real lives and political struggles.

The process of making this zine comprised a series of interviews that helped us reflect on the complexity of privacy for LGBTQIA+ lives. For many people, the Internet is a platform for learning, dialogue, conviviality, and content. It is a powerful space to imagine possible futures, build bridges, admire all colors of the LGBTQIA+ community, and envision new perspectives for life. For those engaging in activist political practices, it is even more: an essential platform for visibility, a political strategy that is widely adopted and legitimized as a form of resistance and a pathway for accomplishments.

The relationship between privacy and visibility is a complex aspect of the LGBTQIA+ experience: visibility as a political strategy, which happens through exposure of one’s own life, is collectively adopted as a form of resistance but at the same time can make people vulnerable to attacks from conservative groups, family, church, neighbors, school peers and work colleagues. In addition, social networks such as Facebook, Snapchat and Youtube — frequently used by LGBTQIA+ folks for the expression of their sexuality, gender identity and personal aesthetic — are also networks that reinforce a centralizing logic: many of them enforce a single online identity with real name verification policies and other measures that largely impact trans identities.

The choice between public or private profiles in social media is also filled with contradictions. On one hand, having a private profile is perceived by several activists as an obstacle to reaching wider audiences. “If it’s hard enough to reach people with a public profile because of Facebook’s algorithms, imagine with a private one!” says one of the interviewees. Another one says that “[my] decision to keep a public profile is because my posts is made available even for those who are not on Facebook”. On the other hand, the awareness of being observed and even threatened on social media hinders the possibilities of what can be posted for every person we interviewed: “I think a lot before posting and try to be very careful”. In a contradictory outcome, the widening of the repertoire of legitimate narratives and aesthetics — one of the major achievements of the visibility strategy — ends up compromised by the possibility of censorship or retaliation.

In this scenario, the central question is how can we potentialize the use of the Internet and the visibility tactics that LGBTQIA+ activists often employ while also reducing the risks of privacy violations and online harassment? The tools and practices of information security can be useful. But more than prescribing tools, what we propose here is to borrow from information security the idea of identity management and imagine it to be more broad, powerful and close to LGBTQIA+ lives and experiences. We propose therefore that using and experimenting with multiple identities can be not only a form of self defense, but also of creating other forms of existence.

One,

no one and

one hundred thousand

Not too long ago, we experimented with an Internet that allowed the exercise of multiple identities. It was a space where we could create different experiences of self and even try being someone else.

For example, it was common for someone to have a blog to write about cooking and another one to discuss porn, each under a different name and personality and linked to different communities and friends. It was also common to keep blogs under fictional identities and stories, close to heteronimity. However, the Internet has changed. And, with it, the way by which we perform our identity has also changed.

Corporations decided that the harvesting and analysis of our personal data was a good business model. This led us to give up our privacy and the services that allowed us to keep anonymity, pseudonyms, and to experiment with identities, for services that demand a sole identity linked to our “real name”.

Facebook’s “real name policy”, for example, forces us to use a single profile to connect and interact in a standardized manner (posting, commenting, liking) with people from the most different circles: family, friends, activists, work colleagues. But we are different people in each of these circles; our affections, attitudes and vocabularies are different. No one is one single person: we are limitless, we contain multitudes. We are trans identities, we are non-binary folks, we are queer folks. The policies enforced by social networks enclose us into single, unified beings and don’t encompass our diversity. They exist so these companies can measure us, quantify us, profile us, monitor us, standardize us, sell us.

Facebook prohibits users from using numbers, punctuation, words or expressions, titles, and characters from other languages in their names. The platform also requires the name to be the one displayed on the user’s ID and, in the case of nicknames, to be “a variation of your authentic name”. In some cases, the company asks users to submit a copy of their ID for verification. Even with the loosening up of some rules in 2015, following pressure from transgender people and drag queens in the U.S., the system continues to trouble trans identities, artists, indigenous people and those who have to hide their names for safety reasons.

The way we use the Internet and online services impacts several aspects of our lives, such as our security, our privacy and how we exercise our identities and subjectivities.

Experimenting with more than one profile on social media and performing different identities in each of them can be a tactic for defense and resistance. It grants us more autonomy over our privacy and the power to choose how and with whom we will share our information and ideas. Keeping different profiles to interact with family, friends and work colleagues allows us, for instance, to choose when, and to whom, we wish to come out, avoiding retaliation and exposure. For those who carry out political and activist practices online, having different profiles is even more recommended. Using a more private profile for your closer family and friends, and a different profile for your online political activity, such as administering pages and exposing injustices, can avoid trolls and conservative groups to access your intimate life and personal information, therefore hindering attacks, threats and hate speech. It requires extra work, but lets our ideas and voices be heard without exposing information about our lives that we wish to keep private.

multiple identities are valuable for the LGBTQIA+ community as more than a defense tactic. Experimenting with them is all the more powerful: it goes beyond security issues, it impacts the very way by which we experience life. We exercise the multiplicity of our identities every day. We perform and are seen in different ways according to the context: for instance, in our families we are often different people from who we are at work. Keeping this in mind and enjoying the possibility of being diverse is an exercise that expands the possible discourses and gives us an opening to be what we want to be, to transform ourselves, to put some movement in life.

Being one, no one, and one hundred thousand. This exercise is embedded in our LGBTQIA+ lives, with our trans identities, our transformations, the pain of staying or leaving the closet. Transforming this into a form of resistance means going way beyond the conflict between privacy and visibility: it is a place of anti-capitalist, counter-hegemonic power. Let’s experiment!

PSEUDONYMIC IDENTITY

I am another

Several reasons can lead someone to use a pseudonym instead of the name displayed on their ID. It can be a way to protect their identity, such as Brazilian writer Machado de Assis, who in the 19th Century used the pseudonym Boas Noites (Good Nights) to criticize slave owners in a section called Bons Dias (Good Days) in the Gazeta de Notícias newspaper. The same happened with several activists during the Brazilian military dictatorship (1964–1985) who used pseudonyms to preserve their personal lives and their families’ and maintain the safety of other activists and their work.

There are more sporadic pseudonyms, which are used in certain situations and later abandoned, and more persistent ones, that can last through one’s entire life. Using pseudonyms for online interactions can be a good strategy to avoid risks and vulnerability to attacks. However, in some situations, pseudonyms can suffer from lack of credibility and reputation. Taking on a pseudonym can also be a way to be someone else, as did David Bowie in many phases of his career. Bowie was Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane, the Thin White Duke. And we can’t forget Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa, who created heteronyms similar to parallel lives, each with a different personality and their own writing.

Whether for experimentation or protection, pick a name and explore the diversity of personalities that live inside you.

ANONYMOUS IDENTITY

I am none,

I am no one

Anonymity is often seen as something bad — something that, for example, prevents the identification of people who are practicing online violence. But anonymity is one of the fundamental principles of freedom of expression and access to information, especially for LGBTQIA+ people, who are those who suffer the most from online hate. The possibility of not revealing our identities is often what allows us to speak up against injustice and violence; for example, report attacks from conservative groups without fearing retaliation. Measures and laws against anonymity can increase human rights violations instead of reducing them. Anonymity can save lives. And it allows us to experience our lives and desires with more freedom: teenagers who are having their first LGBTQIA+ experiences, for example, can use anonymity to research and chat about their sexuality and gender identity without being repressed or forced out of the closet.

Keeping online anonymity requires plenty of attention. Everything we do online generates data and reveals us. So part of the game is being conscious about our digital shadows and hiding. Not because we are criminals or have “something to hide”, but because we are free! Tools such as Tor and Tails help us have fun with this. Do some research and try them out.

COLLECTIVE IDENTITY

I am one hundred

thousand

In 19th Century Great Britain, workers known as Luddites destroyed weaving machinery and set fire to their landlords’ property, demanding for better working and living conditions. The term Luddites comes from Ned Ludd, a mysterious figure that some believe never even existed, but that was probably a character created and incorporated by a group — a collective identity. In 1980s New York City, a group of feminists started adopting a collective identity called Guerilla Girls to unveil the sexism and racism in the art world. By positioning themselves always as a collective, the group was able to maintain the anonymity of its members (“we could be anyone and we are everywhere”) and make their work, and not their individualities, the main focus.

Taking on a collective identity can be a strategy for a group to ensure the anonymity of its members by using collectivity. It is also a way to merge individual skills into a common body, generating more outreach, confidence and reputation. Not to mention a great media strategy.

Being a multitude, blurring the lines of the individual, inhabiting an expanded body. Having a collective voice, subjectivity and identity. Being outside of your times, being a myth, being Luther Blissett, being Buddha. Here lies the power of collective identity.

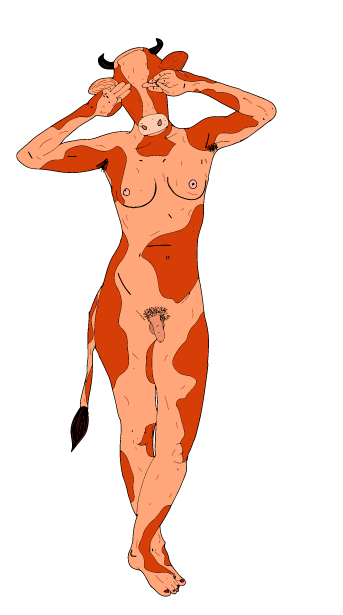

MONSTER IDENTITY

I’m a monster

At first sight, a monster is a bestial, demonic or abject figure. Every culture has an imagery filled with monsters. However, more recent interpretations point to monsters as a social construction, an inverted reflection of the idea of “normality”, often subject to attempts of extermination and complete marginalization. But, at the same time that they are hated or feared, monsters evoke utopias — or dystopias — that reveal the forms of domination and injustice of their time and make a statement about prohibition and difference. In the 1990s, CyberFeminists created video games that were set in dystopian scenarios, where female vengeance against patriarchy was lead by characters such as cybersluts and anarcho cyber-terrorists. Today, Brazilian thinker Jota Mombaça describes the body itself as a monster, a product of social constructions and discourses that is constantly transforming itself and challenging the definitions that try to frame it. Being a monster is embracing the multiplicity of identities that exist within us and going beyond that, knowing that identification and transgression never happen separately.

Taking on a monster identity can open doors to new discourses and strategies, transgressive and subversive towards the status quo, that emerge along with a dystopian aesthetic. Being a monster amplifies the possibilities of our digital practices, discourses and images, and can create connections with other monsters who are also exploring new possibilities for collective emancipation. For artists and activists, monstrosity is a way to denounce and overcome the forms of domination that target those who escape “normality”, doing so from the borders of hegemony. But any body can embrace its monstrosity — in other words, expose the fact that normality is the actual monster that lives only in our imagination.

Credits

Conception

Adriana Azevedo, Amarela, Carolina Munis, Natasha Felizi

Editing and writing

Amarela e Carolina Munis

Translation

Carolina Munis e Guilherme Rocca

Illustration

Guilhermina Augusti

Graphic design and Web development

Steffania Paola

Supported by

Internews

Special thanks

Ariel Nobre, Elvis Justino, Fernanda

Shirakawa, Gabi Juns, Gustavo Bonfiglioli, Luciana

Ferreira, Magô Tonhon, Narria Lemos